How Childhood Trauma Leads to Autoimmune Diseases

How Childhood Trauma Leads to Autoimmune Diseases

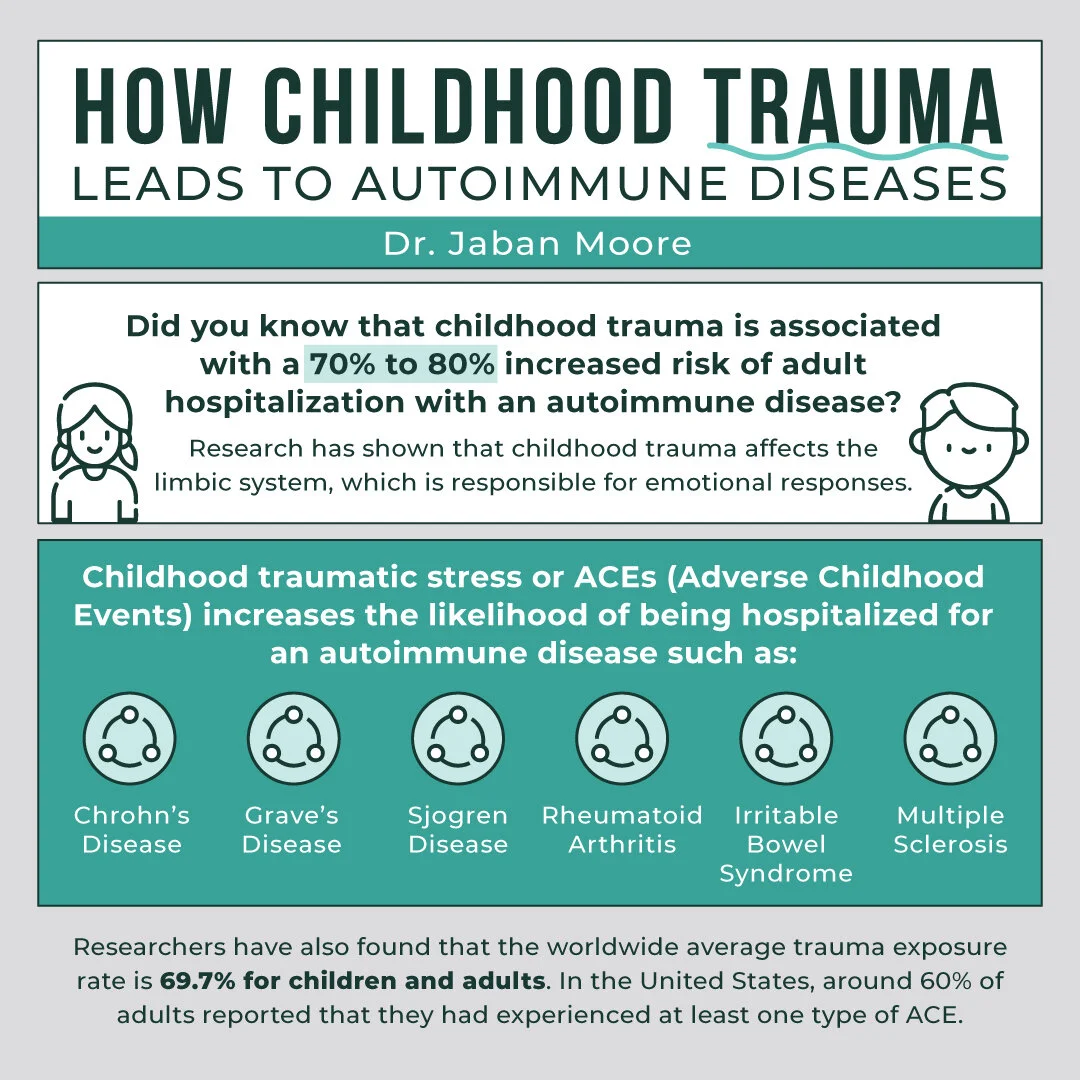

We all know that traumatic experiences can manifest into mental and physical problems in adulthood such as: depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), but did you know that childhood trauma is associated with a 70% to 80% increased risk of adult hospitalization with an autoimmune disease?

Yup, that’s right! Research has shown that childhood trauma affects the limbic system, which is responsible for emotional responses. Because childhood trauma rarely occurs in isolation, the cumulative effect of multiple traumatic experiences continually activates the body’s stress response. This creates an environment where the central nervous system and endocrine system begin to dysfunction and increase the risk for chronic illnesses in adulthood.

The relationship between the nervous, endocrine, and immune interactions have been revealed to be “anatomically and functionally interconnected.” This further proves the common idea that memories can be stored in the body.

What are Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs)?

According to the CDC, ACEs are traumatic events that occur in childhood (0-17 years). Examples of these traumatic events include:

Experiencing violence, abuse, or neglect

Witnessing violence in the home or community

Having a family member attempt or die by suicide

Witnessing hardships such as illness and/or pain

Experiencing illness at a young age

Other aspects of a child’s environment that may threaten their safety, stability, and bonding include:

Growing up in a household with mental health problems

Growing up in a household with substance abuse problems

Growing up in poverty

Parental separation due to divorce, prison, or jail

ACEs are proven to be linked to chronic illnesses, mental health disorders, and substance abuse problems in adulthood.

Click here to read our article about children and chronic illnesses!

The CDC-Kaiser ACE Study:

The CDC-Kaiser ACE Study is one of the largest studies conducted on the development of disease in relation to childhood trauma. From 1995 to 1997, over 17,000 people received physical examinations and completed confidential surveys on their current health status and childhood experiences.

Approximately two-thirds of participants reported at least one ACE, and 1 in 5 participants reported three or more ACEs. This study found that as a person experiences more ACEs, the likelihood of getting “multiple risk factors for several of the leading causes of death in adults” significantly increases. It was found that “ischemic heart disease, cancer, chronic lung disease, skeletal fractures, and liver disease” were common amongst those who experienced childhood trauma.

Click here to read our article on the long-term effects of trauma on the immune system!

How Traumatic Stress Affects the Body:

A 2015 study stated that the “cumulative burden of adverse experiences has been shown to cause negative effects on physiological, cognitive, behavioral, and psychological functions” which can create an environment where rheumatoid arthritis, frequent migraines, insomnia, depression, anxiety, and other chronic symptoms can form.

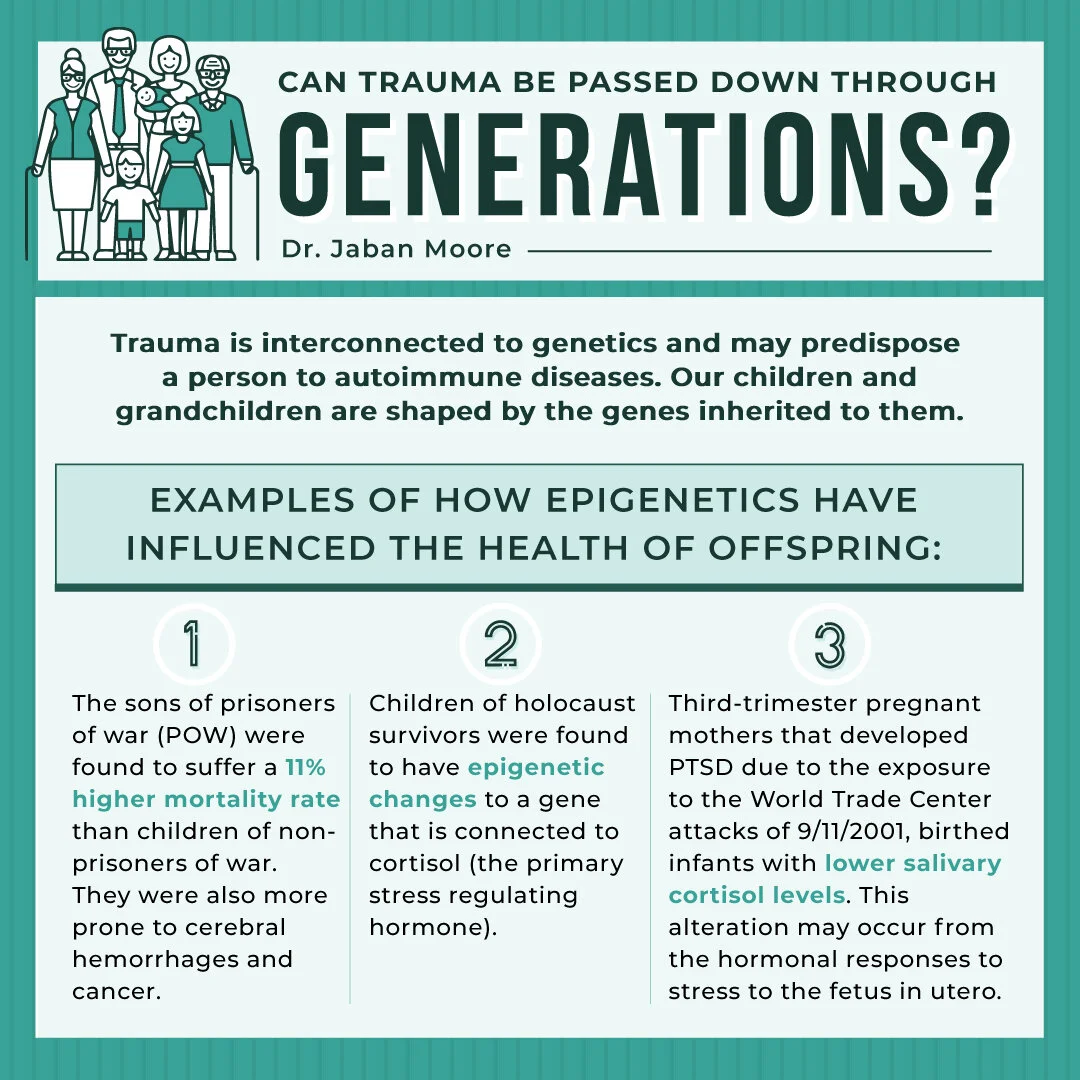

For example, a 2010 study found that holocaust survivors had significantly increased rates of fibromyalgia compared to the rest of the population.

Click here to read our article on the link between trauma and chronic illnesses!

Biologically, stress affects the body at a cellular level. The two primary stress response systems include the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis and the sympathetic nervous system. These systems work together to maintain homeostasis throughout times of chronic stress or during the activation of traumatic experiences.

The HPA axis releases cortisol, the primary stress hormone. This hormone “increases sugars (glucose) in the bloodstream, enhances your brain's use of glucose and increases the availability of substances that repair tissues. Cortisol also curbs functions that would be nonessential or detrimental in a fight-or-flight situation.” Once cortisol is released, a negative feedback loop is prompted to decrease the physical and mental effects of the stress/trauma.

In tolerable stress responses, this negative feedback loop “helps the spike in stress hormones return to baseline quickly and easily.” However, traumatic toxic stress (TTS) and exposure to ACEs can lead to constant activation of stress hormones and disrupt the structure of the immune and endocrine systems.

An imbalance of cortisol levels may result in negative consequences including:

Rheumatoid Arthritis

Sjogren’s Syndrome

Cushing’s Syndrome

Fibromyalgia

Chronic Fatigue Syndrome

There is also evidence that childhood trauma can impact the inflammatory immune system by:

Altering neuroplasticity-related methylation patterns that regulate the central nervous system.

Increasing demethylation of FKBP5, a heat-shock protein that binds and then inhibits the cytosolic glucocorticoid receptor (GR). GR regulates genes that control development, metabolism, and immune response. This leads to GR resistance in adulthood.

Interacting with the rs1360780 risk allele (T) increases the risk for a number of psychiatric disorders. For example, according to a 2019 study, “major depressive disorder (MDD) patients who have been exposed to childhood trauma, the risk allele (T) of rs1360780 has been associated with a lower methylation level of FKBP5 in peripheral blood cells, and lower methylation of FKBP5 has been linked to functional as well as to structural alterations.” This may lead to post-traumatic pain and the diagnosis of pain-related disorders.

Potentially mutating the MAOA gene, a gene that encodes mitochondrial enzymes that catalyzes the breakdown of dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin. This process is essential for proper motor control, emotional regulation, and cognitive function. If dysfunctional, it may cause psychiatric disorders, Huntington’s Disease, restless leg syndrome, ADHD, and antisocial behavior.

Creating chronic inflammation due to chronic stress. This includes cardiovascular disease, rheumatoid arthritis, asthma, psoriasis, metabolic syndrome, fibromyalgia, chronic pain syndromes and hypothyroidism.

Disrupting the vagus nerve’s functions by constantly being in a “fight-or-flight” mode.

The Vagus Nerve

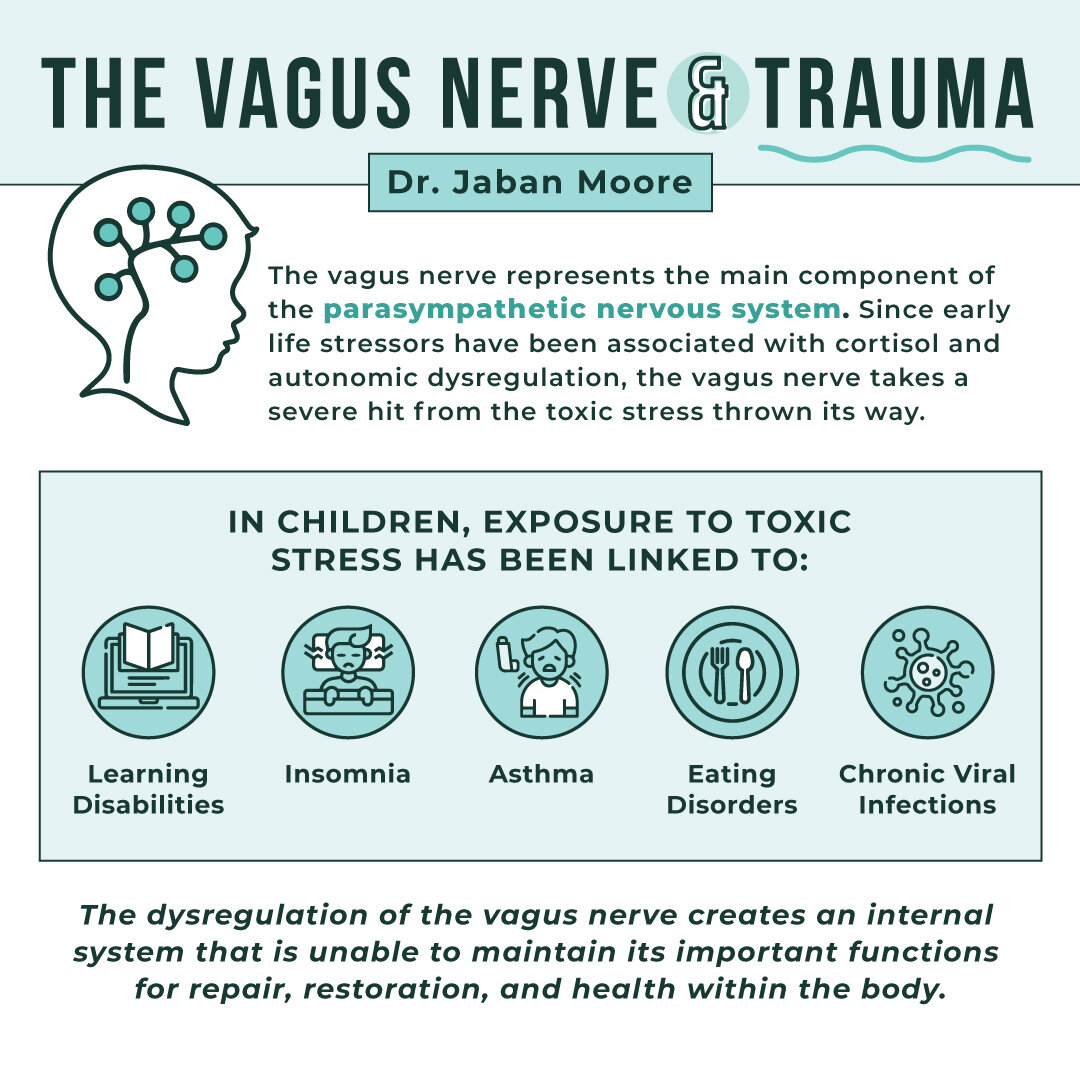

The vagus nerve represents the main component of the parasympathetic nervous system, which “oversees a vast array of crucial bodily functions, including control of mood, immune response, digestion, and heart rate. It establishes one of the connections between the brain and the gastrointestinal tract and sends information about the state of the inner organs to the brain via afferent fibers.” It is also a part of the autonomic nervous system (ANS) that maintains “homeostasis and regulates the functioning of multiple organs—including the heart, lungs, kidneys, salivary glands, and many others—through the dynamic interactions of its sympathetic and parasympathetic branches.”

This nerve has been described as the body’s “second brain” as it directly affects digestion, microbiome support, and communicates to intestinal epithelial cells that protect the gut lining from damage. If this nerve is dysfunctional, it will have an opposite effect on the body and create disharmony in the gut.

So, how does the vagus nerve become dysfunctional after an ACE?

Since “early life stressors have been associated with cortisol and autonomic dysregulation, in addition to an increased risk of adverse health outcomes ranging from cardiovascular disease and lung disease to cancer,” the vagus nerve takes a severe hit from the toxic stress thrown its way. In children, exposure to toxic stress has been linked to learning disabilities, insomnia, asthma, eating disorders, and chronic viral infections. According to a 2017 study, “patients with 4 or more medically unexplained symptoms were similarly more likely to have eating disorders and asthma.”

The vagus nerve is responsible for digestion, heart rate, sleep, motor functions, and sensory perception. A dysregulated immune system caused by toxic stress reduces the vagus nerve’s tone over time which disrupts a person’s general well-being. This toxic stress leads to “elevated levels of corticotropin-releasing hormone, hippocampal cell loss, reduced prefrontal cortical volume, and associated cognitive dysfunction. Children who experience adverse events also develop dysregulated neural responses resulting from chronic or toxic stress.”

The dysregulation of the vagus nerve creates an internal system that is unable to maintain its important functions for repair, restoration, and health within the body. For example, a disrupted vagus nerve is associated with hyperglycemia, risk of new cardiac events, and all-cause mortality.

This challenges the common and unfair notion that chronic illness is “all in the head.” Studies suggest that there are psychological reasons for the manifestation of physical/mental symptoms that are important to recognize in order to heal those who are struggling with chronic illnesses.

A nervous system and vagus nerve that is wired for threat is biologically unable to perform important functions to maintain proper health. According to the same 2017 study, “given the poor, long-term health consequences associated with chronic stress, nervous system dysregulation in children may act as a harbinger of illness and disease in adulthood.”

Is Recovering from ACEs and Nervous System Dysregulation Possible?

It is possible to reduce the effects of childhood trauma and it is possible to healthily rewire the nervous system.

Helpful therapies and practices include:

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

Biofeedback

Physiotherapy

Emotional Freedom Techniques (EFT) / Tapping

Vagus Nerve Exercises (cold exposure, deep breathing, meditation, humming/singing, etc.)

Counciling

If you believe you are dealing with chronic illness, please contact a functional provider. Dr. Jaban Moore, a functional medicine provider, can help you if you are experiencing chronic symptoms.

Please reach out if you are interested in taking your health back! You can give our office a call at (816) 889-9801.

References:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3318917/

https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/aces/index.html

https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/aces/fastfact.html?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2

https://www.ajpmonline.org/article/S0749-3797(98)00017-8/fulltext

https://www.nature.com/articles/pr2015197

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21176421/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3181830/

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00044/full

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4677131/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6857662/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4992603/

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnbeh.2020.00065/full

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5704132/#B9-children-04-00098

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22948482/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10922439/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6761896/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2917081/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1959222/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4928741/